Download this Brief as a PDF: ![]()

English | Français | Português

Summary

Despite earning the inauspicious title in recent years as the shipping corridor with the highest number of piracy attacks in the world, regional responses to piracy and maritime security threats in the Gulf of Guinea, have been fragmentary. Maritime domain awareness remains low, interagency coordination is limited, and intra-regional coordination mechanisms that have been established are often underfunded.

Highlights

- An escalation in piracy and other transnational maritime threats in the Gulf of Guinea has exposed the limited levels of maritime domain awareness in the region.

- The highly fungible nature of maritime security threats means that this challenge cannot be addressed solely by individual states but requires cohesive regional security cooperation.

- While progress has been made, stronger political commitment is needed if regional maritime security cooperation plans are to be operationalized.

The 5,000-nautical mile (nmi) coastline of the wider Gulf of Guinea offers seemingly idyllic conditions for shipping. It is host to numerous natural harbors and is largely devoid of chokepoints and extreme weather conditions. It is also rich in hydrocarbons, fish, and other resources. These attributes provide immense potential for maritime commerce, resource extraction, shipping, and development. Indeed, container traffic in West African ports has grown 14 percent annually since 1995, the fastest of any region in Sub-Saharan Africa.1

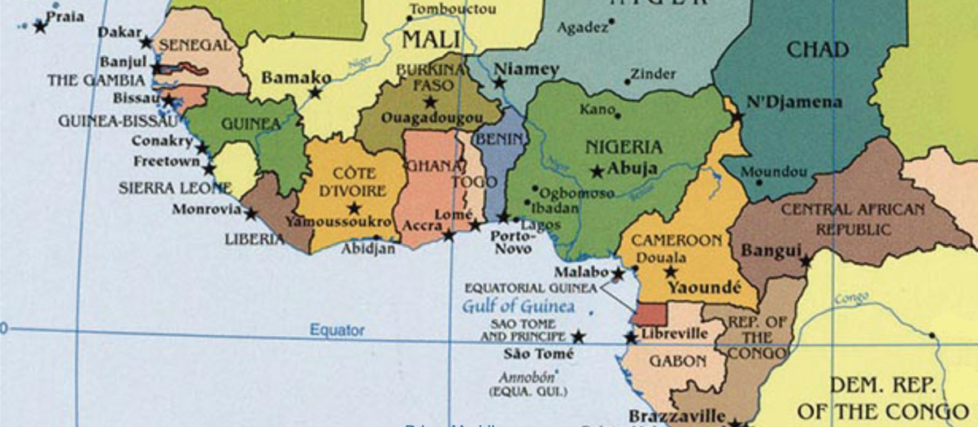

The wider Gulf of Guinea, stretching from Cape Verde to Angola (Figure 1), is the main transit hub and facilitator to the region’s rapid economic growth which has averaged 7 percent since 2012. The Gulf of Guinea has also become a hub for global energy supplies with significant quantities of all petroleum products consumed in Europe, North America, and Asia transiting this waterway.2

This economic boom, however, is threatened. In 2012, the Gulf of Guinea surpassed that of the Gulf of Aden (infamous for high-seas hijackings) as the region with the highest number of reported piracy attacks in the world. These attacks also tended to be more violent. Given the limited maritime security presence off the West African coast, South American narcotics traffickers have found the region an attractive transit route to Europe. Oil theft and illegal bunkering plague the Gulf of Guinea. Nigeria alone loses between 40,000 and 100,000 barrels a day due to theft.3 With 40 percent of the region’s annual catch estimated to be illegal, unregulated, or unreported, West Africa’s waters also endure the highest level of illegal fishing in the world.4

Trade partners have taken note. In 2013, almost all of the estimated $10.2 billion worth of regional trade with the United Kingdom moving through the Gulf of Guinea was declared at risk of theft.5 With the increase in risk to ships, cargo, and seafarers, insurance premiums have soared and companies have taken on additional burdens to secure their ships.

Insufficient state presence in the Gulf of Guinea makes the economic losses incurred by the region difficult to estimate with precision. These are certainly substantial, however. Estimates of the annual cost of piracy to the Gulf of Guinea range from $565 million to $2 billion.6 The strategic development plans of many countries in the region rely on 60 percent of their revenues coming from hydrocarbon resources either sourced from or transiting through the Gulf.7

Governments in the region have been late to realize how their absence in the maritime domain not only costs them untold revenue but also undermines security on land, as criminal activities on the sea start and end onshore. To the extent that the global economy relies on increasingly interdependent shipping and energy supply networks, the maritime threats in the Gulf of Guinea constitute a collective challenge to all stakeholders in the region and internationally.

The Unique Nature of the Gulf of Guinea’s Maritime Insecurity

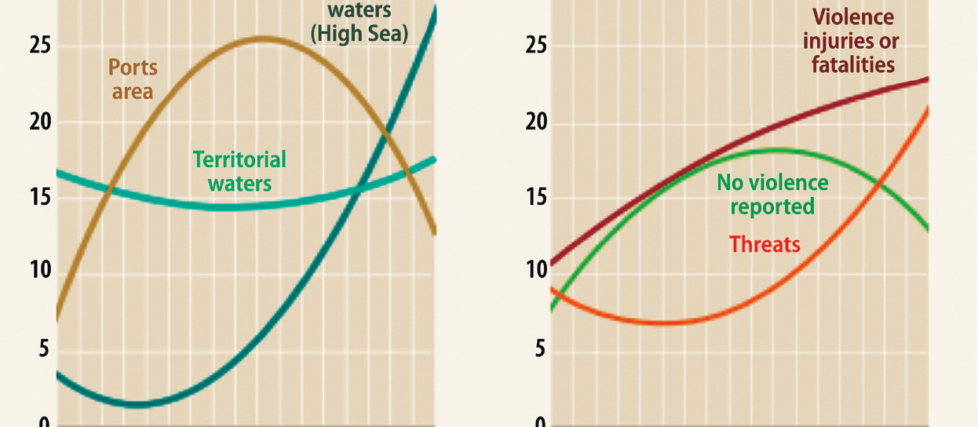

Figure 2: Criminal Incidents Along the Gulf of Guinea Coast, 2006–2013. Source: GSIS, IMO, UNITAR/UNOSAT, 2014.

Piracy attacks (and armed robbery at sea)8 in the Gulf of Guinea comprised a fifth of all recorded maritime incidents globally in 2013. These figures represent only a fraction of the actual attacks in the region as ship owners and governments downplay incidents to avoid increased shipping costs or a reputation for insecurity. Incidents reported to the International Maritime Bureau indicate that the affected area is substantial. Anchorages and approaches to the ports of Bonny and Lagos (Nigeria), Cotonou (Benin), Lomé (Togo), Tema (Ghana), and Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire) are particularly vulnerable with large numbers of merchant ships often loitering in these areas (Figure 2). In the busy port of Lagos, hundreds of vessels loiter for days along the roadsteads (calm areas of water near harbors where ships can anchor) due to the limited capacity of West and Central African ports for offloading. Control measures in the approaches to these ports remain weak. The beaching of 25 ships on the Lagos coast following a rough, 2-hour storm in 2010 revealed that many vessels in harbors are unmanned and unmonitored. The then Director-General of the Nigeria Maritime Administration and Safety Agency (NIMASA) suggested that such boats may also serve as hideouts and blinds for pirates and robbers.

When a vessel is boarded by pirates, equipment and cargo are often stolen. Occasionally members of the crew are kidnapped for ransom. Ships may be hijacked and sailed to distant locations across maritime borders where cargo is transferred to other vessels. Recent attacks in the Gulf of Guinea indicate a preference for ships laden with crude oil and oil products. Such attacks are known to have occurred along the Ghana-to-Angola and Nigeria-to-Côte d’Ivoire axes. For example the MT Kerala was found in waters near Ghana’s Tema Port on January 28, 2014, with a sizable amount of her oil cargo missing after being seized near Luanda 8 days earlier. In other cases, support vessels to offshore installations are attacked, sometimes with such speed and precision as to raise suspicion of complicity of the offshore crews in the theft and illicit sale of oil.

FIGURE 3: Evolution of Types of Attack in the Gulf of Guinea. Source: GISIS, IMO, UNITAR/UNOSAT, 2014.9

Gulf of Guinea piracy is increasingly characterized by violent assaults against vessels and hostage takings—1,871 seafarers were victims of attacks and 279 were taken hostage in 2013 (Figure 3).10 Incidents of fierce resistance to naval patrols have also increased. Pirates aboard a passenger boat opened fire on a Nigerian Navy (NN) craft during a routine patrol along the Cameroonian border in August 2013. Six pirates were killed in the exchange. In another incident just weeks prior, pirates tried to flee the gasoline tanker MT Notre after eight NN vessels surrounded it. Twelve of the 16 pirates were killed and their boat sank during the 30-minute gun battle. In April 2013, two crew members were killed after pirates boarded the SP Brussels off Nigeria’s coast. Just 18 months earlier, five crew were taken hostage when pirates robbed the same vessel while it was 40 miles off the coast of the Niger Delta.

Oil theft is often the result of collusion among local gangs, compromised elements in the oil industry and security agencies, and organized criminal networks from Eastern Europe and Asia.11 While Nigerian nationals have been most involved in the region’s piracy, other Africans, Eastern Europeans, and Filipinos have been arrested in Gulf waters for crude-oil theft, illegal bunkering, and attacks on shipping. In March 2014, 2 Britons, employees of a UK-based maritime security firm, were arrested with 12 Nigerians for attempting to offload crude from a vessel that itself had been seized for stealing oil.12

Building a Collective Maritime Security Response

Attacks on shipping in the Gulf of Guinea have exposed the vulnerability of the region’s maritime space. This has precipitated various countermeasures. In 2010, improvements in operational collaboration between the NN and NIMASA resulted in substantial reductions in attacks around Lagos Harbor. Under the collaboration, jointly manned vessels conduct law enforcement and antipiracy patrols backed with electronic surveillance assets, particularly within the territorial seas and harbor approaches.

Unfortunately, the gains in Nigeria led to increased attacks off the coast of neighboring Benin. After reporting no attacks in 2009 and only 1 in 2010, Benin experienced a surge of more than 20 incidents in 2011.13 As a result, tonnage at Cotonou Port fell by more than 15 percent resulting in a loss of $81 million in customs revenue.14 The development compelled Benin’s President Boni Yayi to request assistance from Nigeria. In September 2011, NN-NIMASA vessels began jointly patrolling waters with Beninese security forces. The number of actual and attempted attacks on ships around Cotonou Port dropped from 20 in 2011 to 2 in 2012 and 0 in 2013. Consequently, shipping activities resurged.

Reflecting the interconnected nature of this threat, enhanced patrolling around Cotonou led to a sharp increase in attacks in 2012 on shipping and hostage taking off the neighboring coasts of Togo (attacks–15, hostages–79) and again Nigeria (attacks–27, hostages–61). Over 80 percent of the attacks recorded in Nigeria occurred in waters off the Niger Delta, where the NN-NIMASA collaboration was less robust. Notably, Togo and Nigeria accounted for over 70 percent of the attacks and hostage taking in West Africa in 2012-2014.

In May 2013, two private maritime security firms collaborated with the NN to launch the Secure Anchorage Area (SAA), which provides security to vessels in a designated area off Lagos Port. The SAA offers armed protection for vessels wishing to either anchor or conduct ship-to-ship transfer operations offshore. In 2014, NIMASA, in collaboration with the NN and the Nigerian Air Force, unveiled a Satellite Surveillance Centre (SSC). The SSC tracks all vessels in Nigerian waters and can identify each vessel’s International Maritime Organization (IMO) number. This initiative complements the existing array of sensors installed along Nigeria’s coastline under the Regional Maritime Awareness Capability (RMAC) program supported by the United States and the United Kingdom. Various other regional and international partners also adopted supportive resolutions and programs, including the African Union, United Nations, European Union, IMO, and G8.

In the meantime, drawing on lessons learned from the Gulf of Aden, the shipping industry created the Maritime Trade Information Sharing Centre for the Gulf of Guinea (MTISC-GOG). With the goal of becoming a dedicated focal point for incident reporting, information sharing, and the latest maritime security guidance, the MTISC-GOG was tested in 2013 and 2014 during the regional maritime exercise Obangame Express. The MTISC-GOG is headquartered at the Regional Maritime University in Accra, Ghana and provides participating vessels with 24-hour-per-day security reportage. It can also provide information to national maritime operational centers in the region and Interpol.

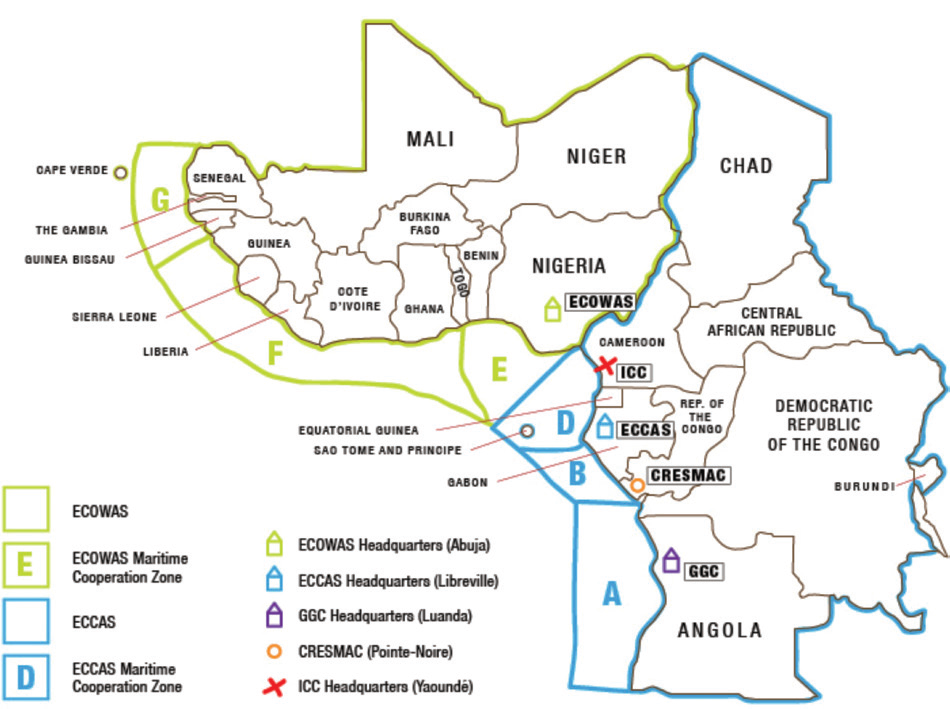

FIGURE 4: Multinational Maritime Coordination Zones in West and Central Africa. Source: International Crisis Group (2014).16

In response to the growing maritime threat, the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) developed an Integrated Strategy for Maritime Security (ISMS) in 2008, which called for a common regional framework for regulating maritime activities off Central Africa. In 2009, it activated the Regional Coordination Center for Maritime Security in Central Africa (CRESMAC) in Pointe-Noire, Republic of Congo. Under the ISMS, CRESMAC is responsible for commanding three centers for multinational coordination (CMCs), one for each zone of Central African waters: Zones A, B, and D (Figure 4). The primary value of this initiative is to bridge information sharing and authorization protocols required in the pursuit of suspect vessels across maritime boundaries.

The CMC for Zone D, operational since 2009, coordinates antipiracy efforts by the navies of Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and São Tomé and Príncipe. This collaboration has resulted in a reduction in maritime crime and hostage taking as well as over 17 citations for illegal fishing that resulted in hefty fines in Cameroon alone.15

There is an ongoing effort to consummate an Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Integrated Maritime Strategy (EIMS) modeled after the ECCAS effort, including creating a regional coordination center for maritime security in West Africa and three zones (E, F, and G) overseen by multinational maritime coordination centers (MMCCs). The pilot for these is ECOWAS’ Zone E (the waters off Benin, Nigeria, and Togo).

The reality of a constantly shifting threat informed the Yaoundé Declaration of June 2013 in which the heads of government from ECOWAS and ECCAS agreed to establish a Maritime Inter-Regional Coordination Center (MICC) in Yaoundé, Cameroon. A “Code of Conduct Concerning the Repression of Piracy, Armed Robbery against Ships, and Illicit Maritime Activity in West and Central Africa” was adopted to further promote collective efforts on information sharing, interdiction, prosecution, and support to victims. Implementation of the nonbinding Code of Conduct has been slow going, however. In particular, the delayed operationalization of the MICC highlights the need for greater political will.

Continuing Challenges

The highly adaptive nature of piracy networks in the Gulf of Guinea mirrors the situation in the Gulf of Aden whereby the gains of the multinational antipiracy effort off the coast of Somalia mutated into expanded threats elsewhere in the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean. While single-state solutions may achieve short-term gains, they are insufficient to curtail the fluid strategies adopted by piracy networks. Accordingly, a strategy of concentrating only on transit vulnerabilities is insufficient as pirates will constantly adapt to circumvent naval countermeasures. The more fundamental issues of how to manage maritime space and to counter what motivates pirates and their support structures on land must also be addressed.

Continental causalities

Man lives on land and not at sea. While the Gulf of Guinea provides an ideal shipping and fishing venue, the ease with which robbers can disappear along the coastline after an attack exposes another, less favorable aspect about the region—limitations of surveillance, intelligence, and community policing in the coastal areas. In particular, political and socioeconomic conditions onshore, especially the growing army of jobless youth, are drivers of piracy in the region. In the Niger Delta, for instance, the government’s amnesty program for ex-militants in 2009 caused an immediate abatement in attacks on shipping. The resurgence in 2013 has been attributed partly to challenges in sustaining gainful employment opportunities to growing numbers of youth in the area.17

Governments are equally obligated to pursue more effective enforcement actions against piracy networks on land. For example, the illicit markets where pirated goods (especially oil) are sold around the world remain largely unimpeded.

Capacity

Operationalizing political, interagency, and interstate commitments to combat piracy and related crimes in waters of the Gulf of Guinea will depend on establishing robust capacity for surveillance, response, and enforcement.

Surveillance

Benin, Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, and Senegal have improved their coastal surveillance assets with the assistance of partners such as the United States and the EU. Unfortunately, the ability to detect vessels without active automatic independent surveillance (AIS) beyond radar range (30–40 nmi) remains a challenge for many states in the region. Similarly, access to affordable broadband and local maintenance capacity to facilitate communication and patrols presents a problem for many states.18

Response

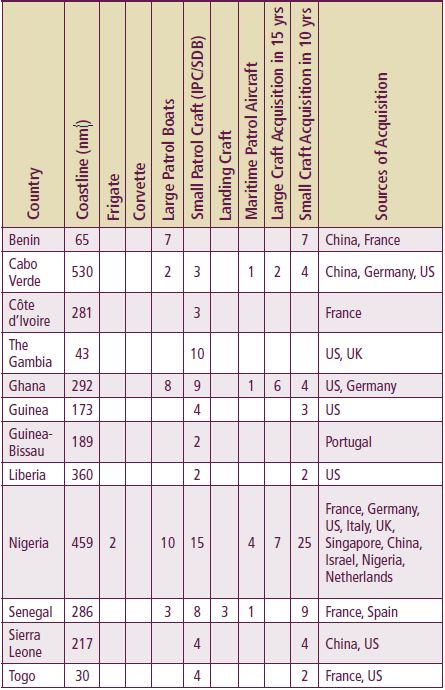

Table 1: Platform Profile of West African Navies and Coast Guards. Source: IHS Jane’s, 2013.21

Central and West African navies and coast guards have limited patrol capacity (Table 1). Even if the entire current inventory of platforms were deployed, there still would not be enough vessels to provide for a sustained patrol of one craft for every 250 nmi of coastline. The variety of equipment suppliers poses additional challenges of interoperability and sustainability of fleet vessels, the majority of which are over 25 years old. Nonetheless, maintaining the availability of these vessels is vital. At the beginning of 2014, the Nigerian government announced a 60-percent drop in crude-oil theft (from 100,000 to about 40,000 barrels a day) due to, among other things, the deployment of newly acquired patrol boats at strategic access routes in the waters of the Niger Delta.19 Additions such as fast Inshore Patrol Craft and Seaward Defence Boats (SDBs), including ex-U.S. Coast Guard cutters, were notable in this regard. Sustaining such modest success requires significant bolstering of patrol inventory with more Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPVs) and coastal patrol boats.

Enforcement

Frustration over the lack of effective prosecution of pirates and maritime criminals is prevalent in many Central and West African states. This stems from an absence of requisite domestic laws for prosecuting piracy and, in other instances, weak penalties and judicial processes. In many states, navies, coast guards, and maritime security agencies lack prosecution powers and rely on the police and other agencies for such a vital element of the enforcement cycle. In the restive Niger Delta, for example, trial for many suspects of oil theft and piracy comes several months after arrest due to insufficient availability of judicial officers.20 During that time, challenges in the preservation of evidence and limitations of detention periods often weigh in favor of the suspects who regain freedom soon after arrest.

Commercialization of Antipiracy Efforts

The increase in attacks to shipping in the Gulf of Guinea has prompted various commercial countermeasures. In Nigeria, oil companies have hired private military and security contractors (PMSCs) to provide protected transit in the waters off the Niger Delta. The exponential rise in the number of PMSCs in recent years demonstrates the lucrativeness of such ventures. The engagement of PMSCs by NIMASA and the government of Togo to guard ports, moreover, underscores the expanding opportunities for PMSCs in the region.

The profit-oriented focus of PMSCs, however, introduces fundamental questions over sovereignty, equity,and governance imperatives. What happens to such profit-oriented ventures when the piracy threat abates? Will such outfits direct sufficient attention to the onshore networks and drivers of piracy, including tracking the products and proceeds of such criminal activities? A scenario whereby PMSCs own more patrol vessels than navies or coast guards raises questions over roles and responsibilities for national security. A concerted effort among the IMO, the regional bodies, and national governments must address these questions before inevitable conflicts of interest and conspiracy theories build up.

Way Forward

Combating piracy and armed attacks on shipping in the Gulf of Guinea requires more effective measures across the piracy cycle from shore-based causes and offshore transit vulnerabilities to shore-based markets for piracy proceeds. Stemming the tide of attacks equally demands more deliberate cross-cutting efforts that incorporate preventive, deterrent, and collaborative measures among national and regional stakeholders.

Maritime Space Management

Improving security is more about the strategic management of maritime space than it is about naval fleets and patrol craft. Central and West African states must define clearer transit corridors and anchorage sites for protection of merchant vessels in their territorial waters and Exclusive Economic Zones, which extend 200 nmi from a country’s coast. This would be akin to the Internationally Recommended Transit Corridor that has functioned well in the Gulf of Aden and has been replicated as a Voluntary Reporting Area in the Gulf of Guinea by the MTISC-GOG. Such arrangements require a combination of regional and national collaboration that the proposed MICC could facilitate. Further to the protected Secured Anchorage Area in Lagos Harbor, similar concepts should be established around approaches to all ports in the region, including enforcement and sanction processes for vessel violations. Such procedures will improve vessel safety as well as simplify the patrol and surveillance demands on maritime authorities. Estimates are that effective maritime domain awareness capability in the area can be realized and sustained at a reasonable cost.22

To advance regional maritime space management, there is a need to fast-track the activation process of the MICC and the pilot Zone E mechanisms. This will facilitate information sharing among law enforcement agencies, maritime commerce stakeholders, and international partners. In particular, the establishment of national maritime operation centers (MOCs) could resolve some difficulties in interagency cooperation among navies and port- and flag-state control authorities.

Enforcement Harmonization

The limited number of piracy-related trials underscores the need for greater harmonization of legal efforts in the region as stated in the Memorandum of Understanding between ECCAS, ECOWAS, and the Gulf of Guinea Commission. To do so, a thorough review of each country’s legal framework should be undertaken to enable each to effectively prosecute piracy perpetrators. Efforts to fast-track extraditions and to synchronize penalties for crimes at sea across jurisdictions would prevent pirates from finding more lenient treatment across coastal boundaries. Members of the judicial system should be trained in coordination with maritime enforcement agencies in order to speed up and standardize the process of evidence collection and preservation to facilitate efficient and fair trials. Creating courts dedicated to handling piracy and sea robbery prosecutions may help minimize these delays.

Internavy Cooperation

Authorization of a standing forum for Zone E heads of navies by the ECOWAS Committee of Chiefs of Defence Staff (CCDS) could provide much-needed synergy for coordination efforts of the region’s navies. This protocol needs to be replicated among other zones under ECOWAS. The Political Affairs, Peace and Security Department of ECOWAS has the responsibility in this regard to encourage the activation of the zonal coordination mechanisms for all member states, including common understandings and prosecutions of cross-border and extraterritorial crimes. Consummation and implementation of the ECOWAS Integrated Maritime Strategy, therefore, deserves the urgent attention and commitment of all stakeholders, including the affected coastal communities.

Asset Requirements

A layered deterrent mechanism characterized by maritime air patrols, ship-borne patrols (made up of OPVs and SDBs), and terrestrial- and satellite-based surveillance assets will be needed to monitor and secure the Gulf of Guinea. A theoretical 100-nmi radar coverage and patrol radius should be assumed for each patrol vessel. For every vessel at sea one should be on standby while another would be undergoing routine maintenance. Based on these assumptions and West Africa’s approximately 3,000-nmi coast, the aggregated minimum OPV requirement for effective deterrence and response amounts to 90 craft. Compared to the current inventory of 32 OPVs/equivalent assets (frigates, corvettes, and large patrol craft as categorized in Table 1), governments should consider the 58-OPV deficit as a working guide on future capitalization efforts. In the relatively calm and open waters of the region, OPVs of under 1,000-ton displacement with minimal weaponry would suffice. SDB requirements would enable effective presence in the approaches to all ports in the region with a similar provision that two additional SDBs be available for each one deployed. States with long coastlines or piracy hotspots should consider acquisition of fixed and rotary wing maritime patrol aircraft. These projections, though ambitious, provide a planning guide for governments, navies, foreign partners, and investors.

Profiling Piracy Networks

Breaking the cyclical chain of attacks on shipping in a cost-effective manner requires a robust capacity for profiling maritime crime and sharing information among stakeholders in the region. Such a capacity would involve monitoring transiting vessels, their crews, and their ownership with a view to profiling suspicious vessels and individuals, including activities in coastal communities. A watch list for suspect vessels as well as human accomplices should be developed, updated, and shared.

Improving security is more about the strategic management of maritime space than it is about naval fleets and patrol craft.

An international campaign to close off markets and financial centers to stolen oil and its proceeds would raise the cost of stealing from the Gulf of Guinea.23 This would require more concerted efforts between Central and West African states and their global partners to identify and sanction criminal networks involved in the laundering of proceeds from piracy and related crimes. Sanctioning vessel owners and organizations known to be the beneficiaries of proceeds from attacks and oil theft would be extremely useful and yet is a significant gap in the collaboration between the EU, Asian, and African states.

Partnership Engagement

More collaboration is needed among international partners and African governments in the international waters around the Gulf of Guinea. Operations Atalanta, Ocean Shield and Combined Task Force 150/151 in the Gulf of Aden and Indian Ocean provide an adaptable template. There would also be value in the US, European and Asian partners strengthening naval and coast guard capacity in the region through effective collaboration with the evolving MICC, MMCC/CMC and MOCs.

Targeted Economic Development on the Coast

The situation in the Niger Delta and widespread poverty in the region underscore the need for more concerted infrastructural development, youth employment generation, and coastal environmental protections. Given that the waters off the Niger Delta account for over half of the piracy attacks recorded in recent years, there is a need to improve economic opportunities for coastal communities there. Likewise, given the socioeconomic impacts of illegal fishing, pollution, and environmental degradation, state and local governments across the region must focus on maritime-related policy matters that directly impact coastal residents. This includes enforcing laws governing foreign companies’ intrastate shipping, proper application of environmental laws, and expanding shipbuilding, fishing, and other industries where significant production deficiencies still exist. Such advancements would reduce the incentives that drive youth into piracy and create shared interests among communities, the state, and the private sector in a secure and vibrant maritime economy. Nigeria’s Petroleum Industry Bill, which incorporates measures aimed at deepening responsible exploitation, improving local community participation, and benefitting host communities with economic, social, and infrastructural development could also emphasize enhanced economic opportunities in coastal areas. At the very least, multinational oil companies should rethink their current community development strategies.

Conclusion

As countries in the Gulf of Guinea increasingly rely on the seas for economic prosperity, the evolving violent attacks on shipping with transnational dimensions call for multilateral remedies. Fast-tracking initiatives such as the MICC, the Zone E MMCC, and other operational models already underway across the region offers a cost-effective and quick-impact approach toward enhancing security in the short term. While acknowledging the necessity of PMSCs as a stopgap measure, there is a need for caution on the part of vessel owners, governments, and regional bodies against the over-commercialization of maritime security. Governments must also uproot the drivers of piracy as well as expand the resources and shared interests in a secure maritime domain. None of these recommendations will gain enough traction to be self-sustaining, however, until the discussion of maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea is raised from the operational to the ministerial level where the purse strings are held. Until there is political will in each Central and West African country to protect the region’s waters, the Gulf of Guinea will remain a challenged security space.

Notes

- ⇑ “Beyond the Bottlenecks: Ports in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Ocean Shipping Consultants, Ltd. for the Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostic project (June 2008), 1.

- ⇑ Adjoa Anyimadu, Maritime Security in the Gulf of Guinea: Lessons Learned from the Indian Ocean, Africa 2013/02 (London: Chatham House, July 2013).

- ⇑ “EU Strategy on the Gulf of Guinea,” press release from the Council of the European Union, March 17, 2014.

- ⇑ Maíra Martini, “Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing and Corruption,” U4 Expert Answer No. 392 (Berlin: Transparency International, September 2013).

- ⇑ “How the lack of security in the Gulf of Guinea affects the UK’s economy,” UK Chamber of Shipping, July 2014.

- ⇑ Jens Vestergaard Madsen, Conor Seyle, Kellie Brandt, Ben Purser, Heather Randall, and Kellie Roy, The State of Maritime Piracy 2013 (Colorado: Oceans Beyond Piracy, 2014), 55. Report of the United Nations assessment mission on piracy in the Gulf of Guinea (7 to 24 November 2011) (UN doc. S/2012/45, January 2012), 11.

- ⇑ Loïc Moudouma, Lead Maritime Security Expert, ECCAS, and Commander in the Navy of Gabon (panelist discussion at the National Defense University’s Round Table, “Africa’s Security and the United States: Converging Interests and Expanding Partnership,” Fort McNair, Washington, DC, July 29, 2014).

- ⇑ The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) defines piracy as an attack on a vessel “outside the jurisdiction of any state,” or beyond 12 nmi from shore. The International Maritime Organization (IMO) defines armed robbery as an attack on a vessel made within 12 nmi—within the jurisdiction of the state. For simplicity, references to piracy in this paper comprise all attacks on vessels.

- ⇑ UNOSAT Global Report on Maritime Piracy: a geospatial analysis 1995–2013 (New York: UNITAR, 2014), 32.

- ⇑ Madsen et al., 68.

- ⇑ Tim Cocks, “Balkans, Singapore Top Buyers of Stolen Nigerian Oil – Expert,” Reuters, October 22, 2012. Christina Katsouris and Aaron Sayne, Nigeria’s Criminal Crude: International Options to Combat the Export of Stolen Oil, Chatham House Report (London: Royal Institute of International Affairs, September 2013), 33–36.

- ⇑ Samuel Oyadongha, “JTF Arrests 2 Britons, 12 Nigerians for Illegal Bunkering,” Vanguard, March 29, 2014.

- ⇑ Report of the United Nations, 3.

- ⇑ Ibid, 5.

- ⇑ Sylvestre Fonkoua Mbah, “The Multinational Center of Coordination, Zone D” (presentation delivered at OPV Africa Conference, Lagos, Nigeria, August 26–29, 2013).

- ⇑ Thierry Vircoulon & Violette Tournier, “Gulf of Guinea: A Regional Solution to Piracy?” International Crisis Group’s In Pursuit of Peace Blog, September 4, 2014.

- ⇑ “Bryan Abell, “Return to Chaos: The 2013 Resurgence of Nigerian Piracy and 2014 Forecast,” Captain Blog, January 14, 2014.

- ⇑ Augustus Vogel, “Investing in Science and Technology to Meet Africa’s Maritime Security Challenges,” Africa Security Brief No. 10 (July 2011).

- ⇑ Anayo Ezugwu, “New Initiatives to Curb Crude Oil Theft,” Real News, January 27, 2014.

- ⇑ Author interview with Mr. Desmond Agu, Commander, Nigerian Security and Civil Defence Corps, Bayela State, Nigeria, December 19, 2013.

- ⇑ IHS Jane’s Fighting Ships 2013–2014, ed. Commodore Stephen Saunders RN (London: Jane’s Information Group, July 2013), 1021.

- ⇑ Commodore Adeniyi Adejimi Osinowo, “Africa Partnership Station Helps All Sides,” Proceedings 137/7/1,301 (MD: U.S. Naval Institute, July 2011), 60.

- ⇑ Katsouris and Sayne, ix.

Rear Admiral Adeniyi Adejimi Osinowo is an officer in the Nigeria Navy. His three decades of experience include participation in operations and sea exercises in the Gulf of Guinea, the Mediterranean, and the Caribbean. He served as an expert in the development of the Africa Integrated Maritime Strategy 2050.